Karakalpakstan - Toprak Kala Fortress

Toprak Kala fortress is located 212 metres west of the Nukus – Khorezm highway, 3.6 kilometres north and slightly west of Shark Yulduzi settlement, 12.3 kilometres northwest of Bustan settlement and 26.9 kilometres north and slightly east of Beruni settlement in Ellikala district of the Republic of Karakalpakstan.

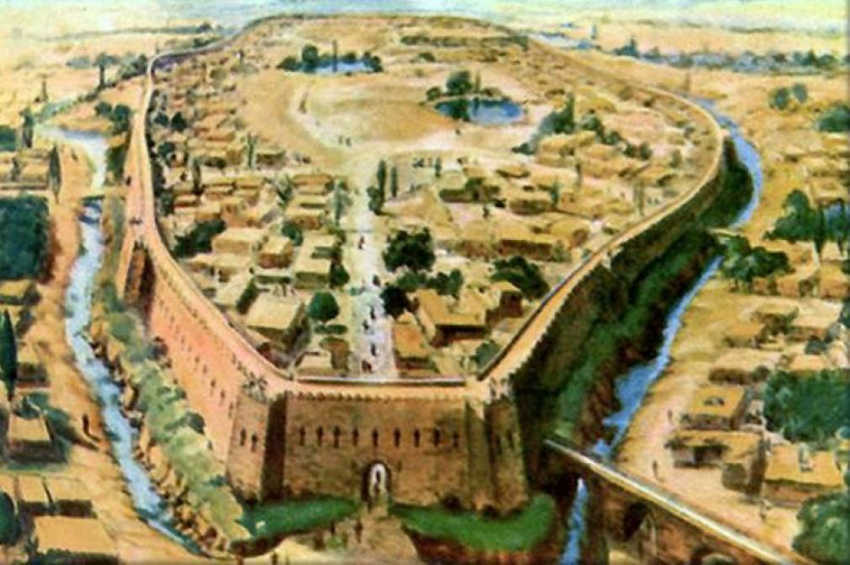

The Toprak Kala fortress is located Just a few kilometres from Urgench in the direction of the city of Khiva, where the palace of the Khorezmshakhs was located in the III-IV century AD. The ancient fortress is now a construction of rectangular shape, whose dimensions are 350 × 500 metres.

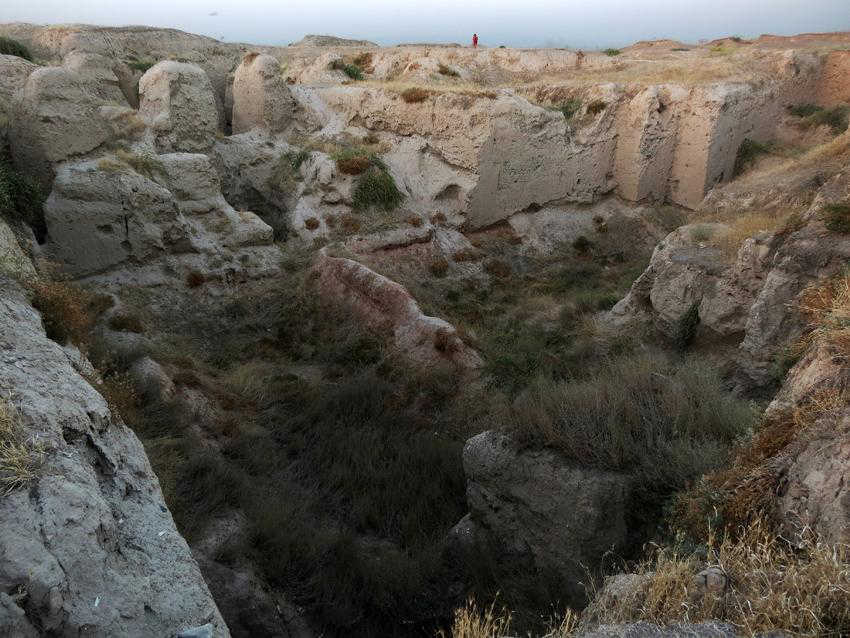

Despite numerous destructions, the height of the fortress walls reaches almost ten metres in some places. Of the entire complex, only the south-eastern corner of the fortress is well preserved, but even this gives us an idea of the size of the oldest building.

In 1940, exploratory work was carried out on the fortress: a large stratigraphic pit was made in the south-eastern part of the town, its plan was compiled, excavation material was collected.

In 1950, a small excavation was laid out on the western fortification wall. Then there was a pause in the work on the monument, which was not resumed until 1965 and lasted for three years until 1975.

The Toprak Kala settlement covers an area of 500 by 350 metres. Rectangular in plan, it is surrounded by fortress walls that are preserved in the form of shafts, reaching 8-9 metres in some places.

The walls had numerous square towers with rounded corners and a wide ditch. It is noted that the fortifications of the city underwent significant reconstruction.

Originally, it was a fortification with a two-storey corridor with a vaulted basement and arrow-shaped embrasures on the upper floor. The outer wall of the rampart was decorated with lobes and niches between the lobes.

After reconstruction, the ground floor of the corridor was walled up and converted into a six-metre-high plinth, into which the earlier towers were also walled up. The walls of the one-storey gallery were replaced by shallow slit windows with cavities and lobes. The new towers had a semicircular shape.

In the middle of the southern wall, the entrance to the citadel, was a complex gatehouse, which was also rebuilt. From it throughout the city to the citadel, which was in the northwest corner of the fortress, ran a central street about 9 metres wide; it divided the city into two parts, which in turn were divided by side streets about 4.5 metres wide into 5 square blocks of 100×40 metres.

Excavations were carried out in two quarters, marked A and B, located in the western half of the city. Layers dating from the 2nd to the 6th century AD were uncovered; however, judging by the presence of certain types of coins of Choresmian coinage and pottery, the site of the settlement must have been covered by the earlier layers.

Three horizons are distinguished in the stratigraphic layers of the settlement. The upper quarter has not been preserved. One of the quarters, A, was found to be completely occupied by the temple buildings that had traditionally been erected there throughout the history of the city.

The total temple area was 42 x 42 metres. Inside it were three buildings built according to the same plan: a chain of rooms with wooden thresholds and door frames stretched from west to east.

One of them, the large Building I, which measured 35 x 18 metres and faced the street between Blocks A and B, consisted of three large rooms measuring 11 x 4 metres. Its walls were up to 3 metres thick.

Finally, the western and apparently most important room, one of the walls had an arched hearth niche and other architectural features, it was a temple of fire. In the other building, called Building II, the horns of a ram khar were found, decorated with gilded bronze bracelets, around which numerous offerings were placed on the floor – shards and whole glass vessels, jewellery, beads, pendants, rings, etc.

A fragment of a painted alabaster sculpture representing a person was also found, as well as fragments of gold foil, etc. Both buildings have been dated to the IV-VI century, but Building II is from a later period within the above time interval.

In the residential block, a multi-room dwelling was uncovered, which included living rooms, storerooms, courtyards, etc. Traces of handicrafts were recorded in the premises facing the side and middle streets.

Especially in the early period of the city’s existence, there were workshops (or workshop) for making bows. As a result of the excavations at the site of the ancient city, we have obtained diverse and rich material that allows us to characterise in detail the hitherto little-studied Kushan-Afrikid culture of ancient Khorezm, as well as to provide important information about the history of the ancient cities of Khorezm.

The main body of the palace was built on a mud-brick base into which the northern and western city walls extended. It had the shape of a truncated pyramid with a height of 14.3 metres and a base area of 80 x 80 metres.

Soon three more arrays were added on plinths up to 25 metres high, with areas of 35 x 35 metres, 40 x 35 metres and 35 x 20 metres. The outer walls of the original palace project 1.5 metres beyond the edge of the platform.

Over a considerable distance they are washed away, but where further massifs adjoin they remain up to a height of 7.5 metres before crumbling away, probably at least 9 metres. The façades were decorated with a system of vertical projections and niches and covered with alabaster whitewash.

The entrance was on the east side with a flight of steps around the entrance tower. About 100 partially preserved rooms on the first floor of the central body and some rooms on the second floor. The walls of the rooms were preserved to their full height in the peripheral areas and covered with applied plinths, but in the central part of the complex they were largely washed away.

The ceilings were vaulted, mostly made of trapezoidal mud bricks, and the beams were flat. In large rooms, the beams were supported by wooden columns with stone plinths. In the internal layout of the palace we can see the division into three main complexes, which were almost isolated from each other.

On the south-eastern side of the palace was a complex of 12 unadorned rooms in which we find washing vessels, remains of the palace archives and weapon storage. Along the southern edge of the palace, along a long corridor separated by a burnt brick wall, were four similar blocks consisting of two rooms and a staircase leading upwards.

The corridor led to a small courtyard with circular niches, around which four two-chambered sanctuaries with two-storey altars and niches were grouped. In one of them, wall paintings depicting a mourning scene have been preserved.

This suggests that the shrines were intended for funeral rites performed by priests whose flats were connected to the corridor. The largest part of the palace was occupied by the complex of ceremonial rooms and sanctuaries associated with various aspects of royal culture.

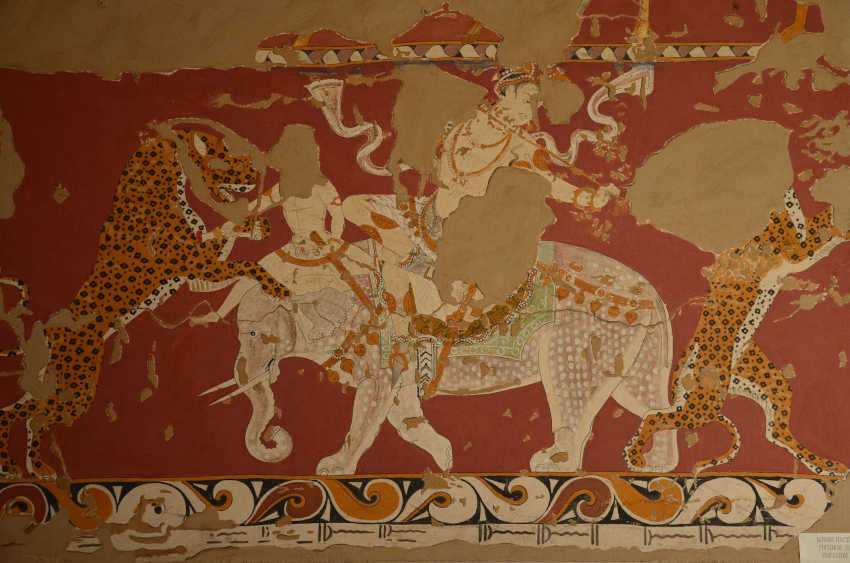

The walls were decorated with frescoes and five halls were decorated with the clay polychrome bas-reliefs. Only an insignificant part of the former decoration has come down to us in the rubble / what was saved during the excavations in the 1940s is now in the State Hermitage Museum.

However, it is possible to imagine the furnishings and presumably to determine the function of several rooms.

The “Hall of Kings” in the Toprak-Kala fortress was a dynastic sanctuary where fire burned on an altar in front of large images of 23 kings of Khorezm (unlike the others, these sculptures are full-size). They were on soles divided by partitions into a number of boxes.

In each of them, in addition to the statue of the king, were two female and one male high reliefs.

“Hall of Victories” at Toprak-Kala Fortress – bears on its walls bas-reliefs of seated tsars and goddesses flying beside them. These compositions /save only legs of figures/ probably recalled the images on the coins depicting the moment of handing over the rulers with badges of royal dignity.

“Hall of the dark-skinned warriors” at the Toprak kala fortress. Here, the bas-relief images of the kings standing in niches under clay overlays in the form of huge stylised rams’ horns. Dark-skinned warriors (the location of these small figures cannot be precisely determined) trumpeted the glory of the kings. The decoration of the hall sanctuary was apparently subordinate to the idea of military glory and good fortune.

The “Hall of the Deer” in the Toprak kala fortress was decorated with figures of these animals, above which was a belt with images of griffins. Other bas-relief fragments include fruits of pomegranates, vines, etc. The decoration may have conveyed the life cycle of the plant and animal kingdoms.

In the “Hall of Dancing Masks” at Toprak-Kala Fortress, images of men and women dancing in pairs are partially preserved on the walls. The main niche apparently contained the image of a great goddess with a predator (individual fragments have been found).

The other two large niches may have contained companion gods. An altar podium is open in the middle of the hall. The hall was, as one can think, intended for the performance of mysteries symbolising the king’s connection with the fertile forces of nature.

The importance of this sanctuary is indicated by the fact that it was directly connected to the main part of the throne ensemble. This ensemble consisted of a forecourt and an aivan divided by a three-arched portal.

Under the central arch, the diagonals of the square in which the entire main palace is inscribed crossed. The north-western additional field enclosed a large square room, which has now been almost completely washed away.

It was crossed by corridors on whose walls waves and fish were depicted. Perhaps the north-western field was a sanctuary dedicated to the water element. The southern arrangement also had a ceremonial and probably a cultic purpose.

Traces of painting and the remains of a rectangular podium were found in the axial space. The north-eastern massif consisted of 8 very high, elongated rooms covered by vaults, some of whose arches have surprisingly survived to the present day.

The purpose of these rooms, which were undecorated and created shortly after construction, remains unclear. The most important find found in the palace are the ancient documents from Khorezmia.

The origin of various objects and products was recorded on the skin; several dates have been preserved, the earliest being 188 and 252 years of the Khorezmian era, which began in the first half of the first century AD.

The records on the tree are lists of able-bodied and unemployable freemen and slaves who were members of various Khorezmian families. The palace, which had primarily a sacred purpose, was abandoned in the early 4th century AD and, after partial repair, was used as a city citadel.

Most of the household finds belong to this period. The exploration of the northern complex of Toprak-kala in 1976 – 1979 showed that it is a group of buildings located outside the settlement of Toprak-kala about 100 m north of the palace excavated by S. P. Tolstov in 1946 – 1950 and additionally explored in 1967 – 1972.

The buildings of the northern complex cover an area of about 12 hectares. The length of the chain of buildings extends along the north-south axis – 350 metres. the same length of the array, aligned in the latitudinal direction. There are 10 buildings, but this figure is provisional.

It is likely to become smaller as excavations have shown a tendency to group individual ramparts into very large palatial structures. The closest building to the “High Palace” is building No. 1 of the northern complex, which was excavated between 1976 and 1979 and is located on a west-east axis.

The size of the building is determined by the area of the base of about 160 – 180 x 50 metres, the height of which reaches about 2.5 metres. Approximately 50 rooms are cleared here, these are the large palatial halls, but also small utility rooms.

The halls and small rooms had paintings on the walls. However, only a few have survived. One room was dominated by coloured ornaments on a white and black background. Depicted were large and small rosettes, lotuses, tulips, lianas, etc.

In another room, the ornaments had a completely different character and imitated the geometric patterns of textiles or carpets / the image of fringes was also preserved. In a third room in a large hall, tapes were found on the walls forming a rhombic grid.

In another room the remains of a sculpture were found, unfortunately only fragments, representing the lower legs and the dress. Also found in this room was a large /0.70×0.70 m/ piece of grey marble with well-polished sides (0.2 m) and with a chipped top.

It is either part of a sculpture or a pedestal for an altar. It is therefore a palace complex. There were also some utility rooms – the eastern part of the building, but they are poorly preserved. Part of the area with pits for vessels, ashes, waste and fireplaces is preserved.

In the second building, which has the preserved dimensions of 70 by 35 metres and a plinth height of 1.2 metres, 25 rooms are preserved. There are also halls and small rooms. The walls in most of the rooms are covered with white plaster. However, there are also fragments of colour paintings in different colours (red, pink, blue, grey).

Here, as in the first building, there are some halls with wooden bases of columns. Instead of the bases of columns made of polymitic sandstone, which had a three-tiered base on which the second piece of a moulded form was installed, the bases of columns are preserved, which were deeply traditional for the architecture of the time.

The cast pieces have fallen off the bases. There are a number of large halls without column bases. These appear to have been open spaces. In one of the halls there is a painting of floral and geometric ornaments as a base under the floor of the room.

This suggests that the palace may have been rebuilt. On the north wall of the second building are two towers No.1 and No.2, which are rectangular monolithic bases of some surviving buildings. Their function is not clear.

Their fortification significance may be assumed if the courtyard on the east side can be proved. West of buildings No. 1 and No. 2, in the meridian direction, building No. 7 has dimensions of about 100 by 30 metres and heights of 10 to 150 centimetres in the southern part and up to 5.5 metres in the northern part.

More than 50 rooms are cleared in it. In the southern part we have three three-room complexes, which are very similar to the complexes in the south-western part of the “High Palace”. In the northern part, the lower rooms were walled up. Two staircases led to the second floor.

Thick walls and bricked-in cones had preserved the ground floor to the present day. In one of the pits it was found that the base of building 7 stood on the ground, while the base of building 2 was underlaid at the joint with a layer of cultural material about 30 centimetres thick. It follows that Building No. 2 was built later than Building No. 7.

It seems that buildings No. 1, 3 and 7 were built at the same time, as their plinths were identical up to 2.5 m, while building No. 2 was built somewhat later. Only the plinth of building no. 3 has not been preserved. The plinth is 80 metres east of building No. 7 and 8-10 metres north of building No. 2.

Buildings No. 4, 5, 6 are extended in meridional direction north of building No. 3. Only the bases of the premises are left of them. Between buildings no. 7 and 2 and 3 is the northern courtyard of the complex. To the west of building no. 7, buildings nos. 8, 9 and 10 are extended in the width direction.

Between buildings 8, 9 and 10 are the courtyards; and finally, further west, is the shaft of the roofing system, in which two Huvishka coins were found. In addition, a coin dating back to the time of Vima Qadfiza was found in 1978 on the floor of Room 24 of Building No. 1.

A small golden head of a lion cub 3 x 2.5 cm was found in the passageway to room No. 24. In room No. 3 of building No. 1, an alabaster mould for making a bas-relief image of “satyrs” was found.

In the heart of Central Asia, in the valley of the river Ili, in the Almaty region, lies the Altyn Emel State National Park. The park was established in 1996 to preserve the unique natural complex of the area.

In the heart of Central Asia, in the valley of the river Ili, in the Almaty region, lies the Altyn Emel State National Park. The park was established in 1996 to preserve the unique natural complex of the area. The Ascension Cathedral (Senkov Cathedral) in Almaty was built in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by the Russian architects Borisoglebsky, Stepanov, Troparevsky and Senkov. After the earthquake of 1910, which destroyed many buildings in Almaty, this is the only structure that survived.

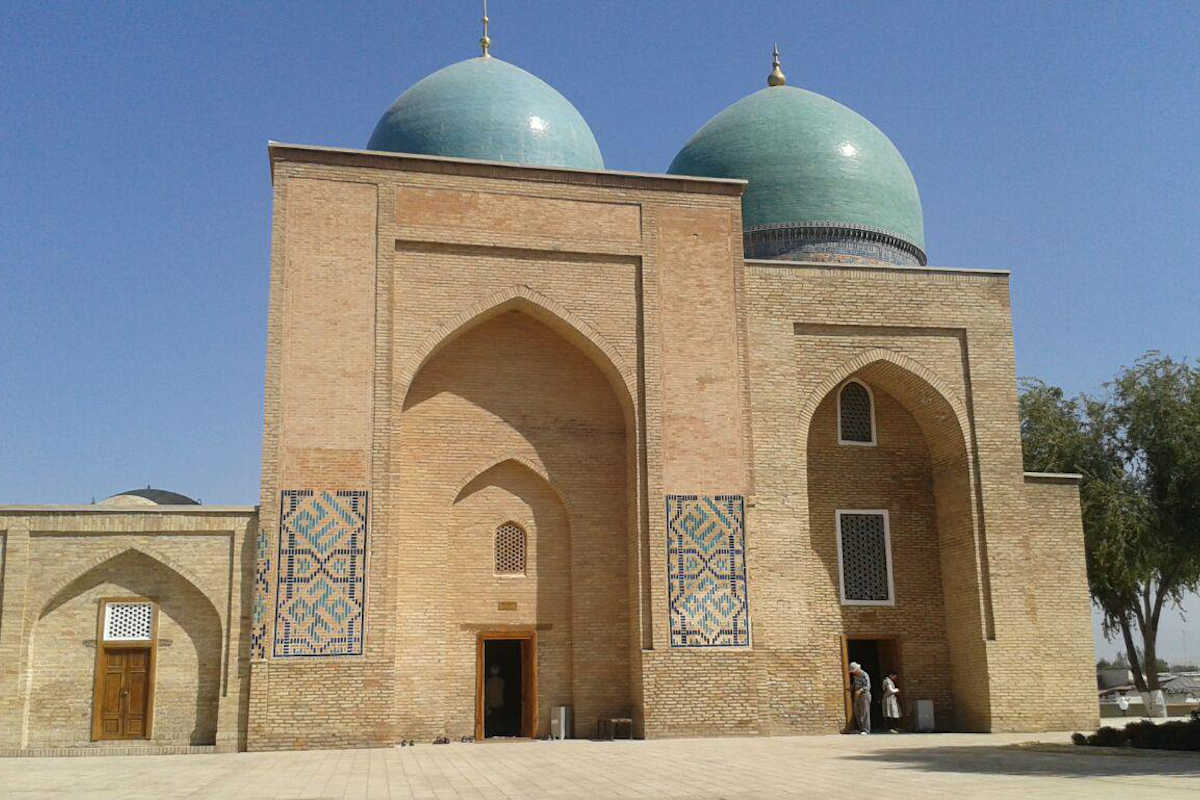

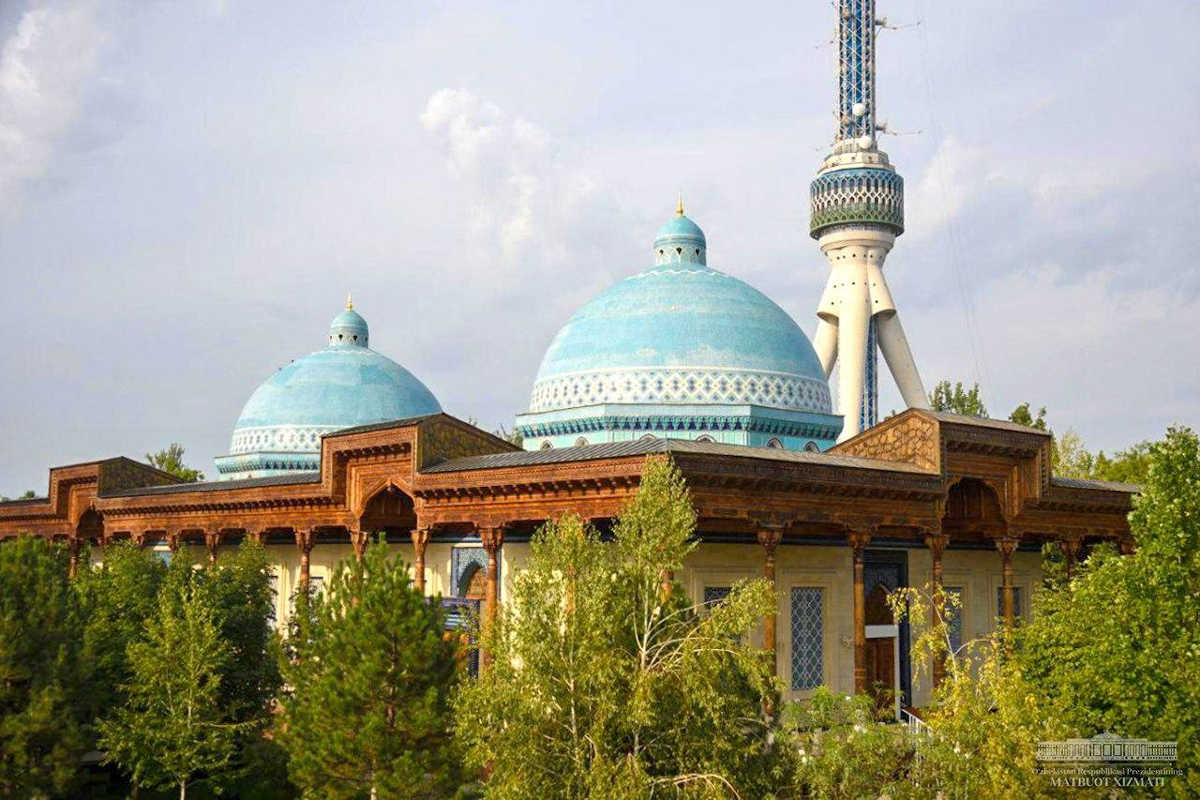

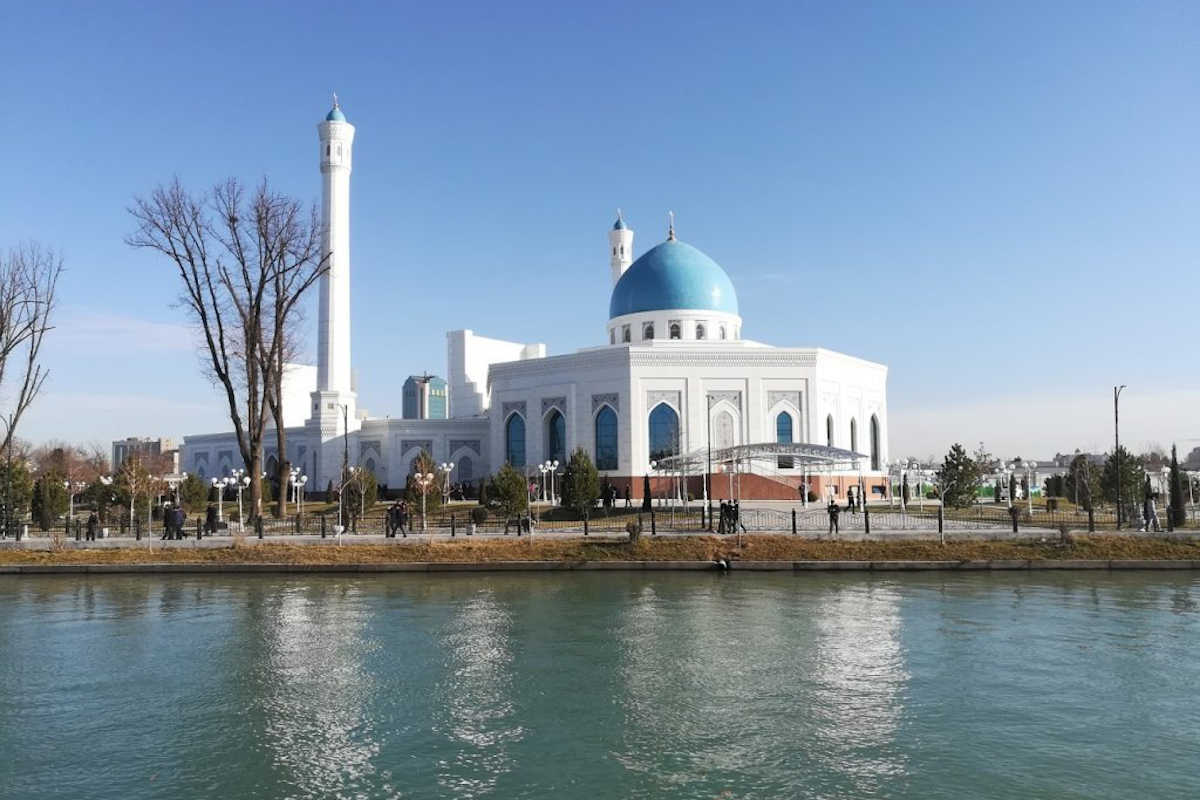

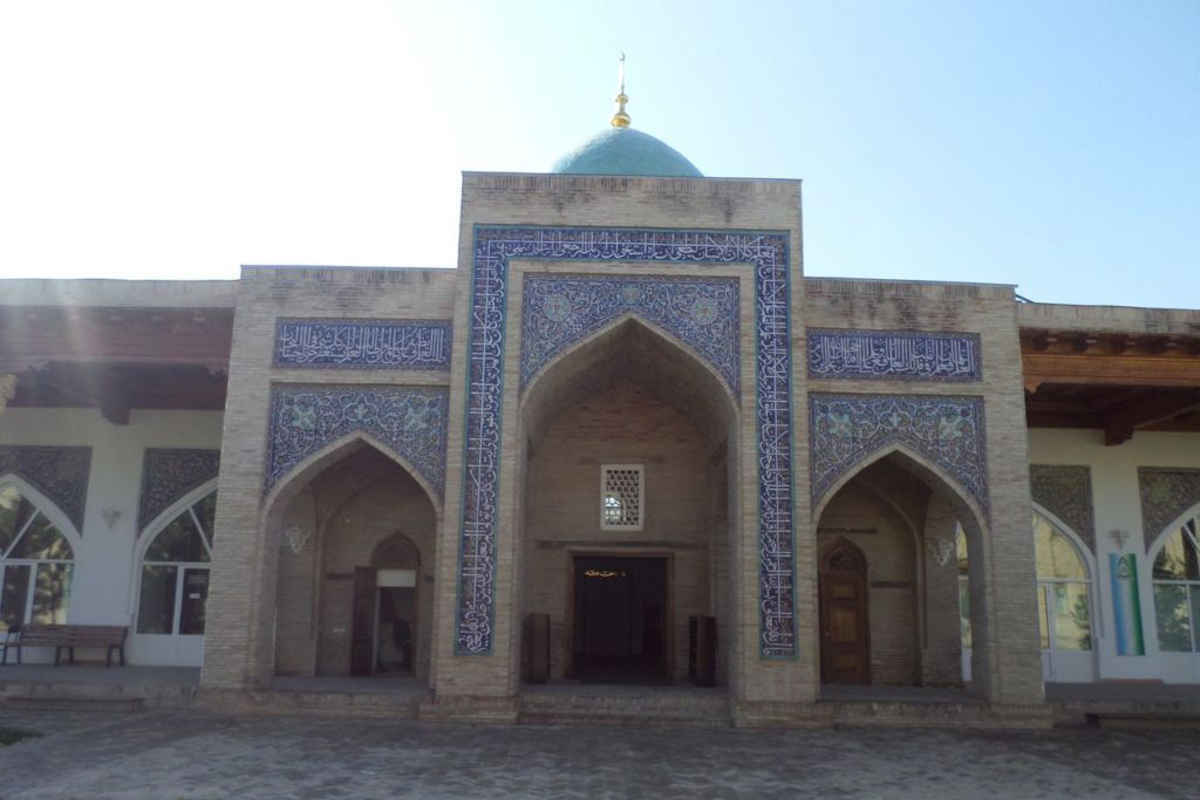

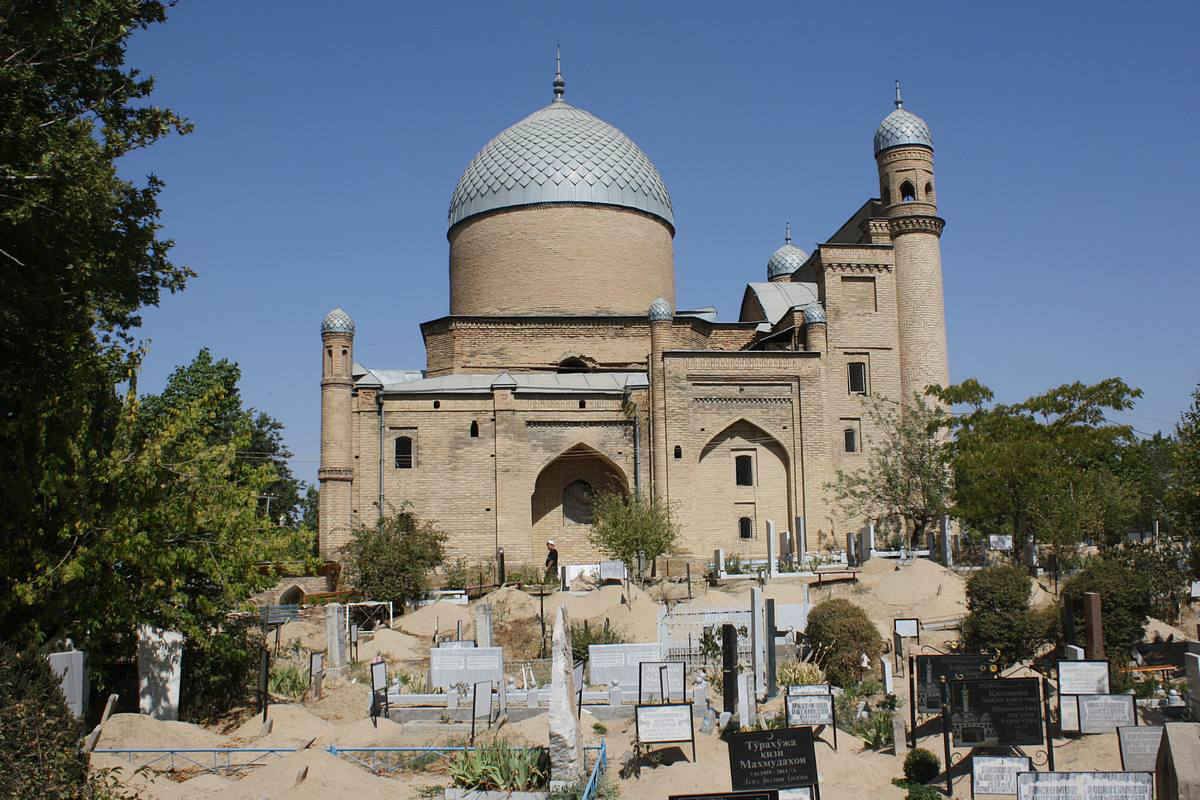

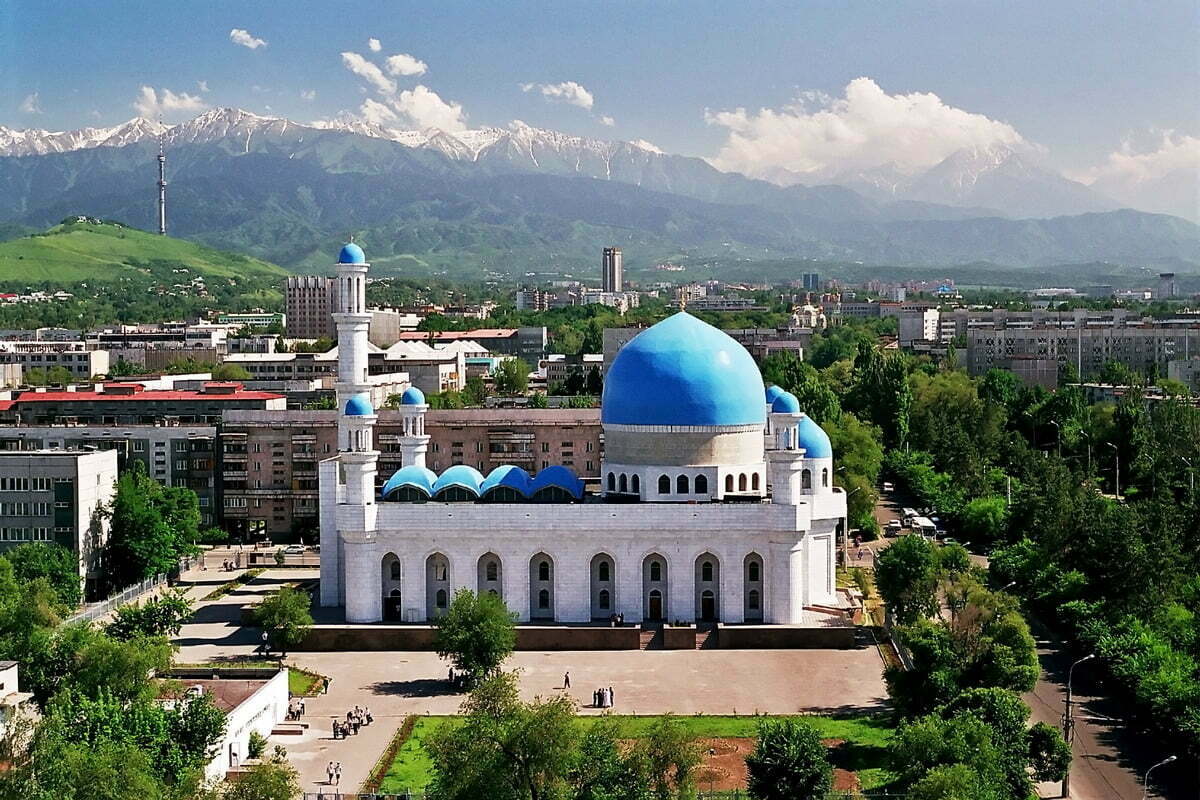

The Ascension Cathedral (Senkov Cathedral) in Almaty was built in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by the Russian architects Borisoglebsky, Stepanov, Troparevsky and Senkov. After the earthquake of 1910, which destroyed many buildings in Almaty, this is the only structure that survived. The main religion in Kazakhstan is Islam. The Kazakh people have practised the Islamic religion for more than a thousand years. There are more than 20 mosques in the city, but the Friday Mosque on Pushkin Street is the centre of the city’s spiritual world. The Central Mosque of Almaty is one of the largest mosques in Kazakhstan. The mosque was put into operation in 1999. The personal support of the Head of State N.A. Nazarbayev played an important role in speeding up the completion of the construction and handing over the mosque for use by the faithful. The architects are: Baimagambetov and Sharapiev.

The main religion in Kazakhstan is Islam. The Kazakh people have practised the Islamic religion for more than a thousand years. There are more than 20 mosques in the city, but the Friday Mosque on Pushkin Street is the centre of the city’s spiritual world. The Central Mosque of Almaty is one of the largest mosques in Kazakhstan. The mosque was put into operation in 1999. The personal support of the Head of State N.A. Nazarbayev played an important role in speeding up the completion of the construction and handing over the mosque for use by the faithful. The architects are: Baimagambetov and Sharapiev. The Charyn State National Park in the Almaty region was established to preserve natural landscapes of special ecological, historical and aesthetic value. Due to the favourable combination of various functional purposes of the areas included in the park, they can be used for scientific, educational, pedagogical, cultural and recreational purposes. The territory of the national park includes the valley of the Charyn River.

The Charyn State National Park in the Almaty region was established to preserve natural landscapes of special ecological, historical and aesthetic value. Due to the favourable combination of various functional purposes of the areas included in the park, they can be used for scientific, educational, pedagogical, cultural and recreational purposes. The territory of the national park includes the valley of the Charyn River. Geok Tepe is 40 km west of Ashgabat. The famous Battle of Geok Tepe took place on the territory of the fortress. The fortress was captured under the command of the Russian general Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev.

Geok Tepe is 40 km west of Ashgabat. The famous Battle of Geok Tepe took place on the territory of the fortress. The fortress was captured under the command of the Russian general Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev. Nisa is an old city whose ruins are located near the village of Bagir, 18 km west of Ashgabat, the capital of Turkmenistan. It consists of two sites: New Nisa, a Parthian city in the valley, and Old Nisa, a royal fortress on a plateau.

Nisa is an old city whose ruins are located near the village of Bagir, 18 km west of Ashgabat, the capital of Turkmenistan. It consists of two sites: New Nisa, a Parthian city in the valley, and Old Nisa, a royal fortress on a plateau. The settlement of Anau is located 12 km east of Ashgabat. Archaeological findings indicate that the settlement of Anau already existed in the Neolithic period (IV-III millennium BC).

The settlement of Anau is located 12 km east of Ashgabat. Archaeological findings indicate that the settlement of Anau already existed in the Neolithic period (IV-III millennium BC).

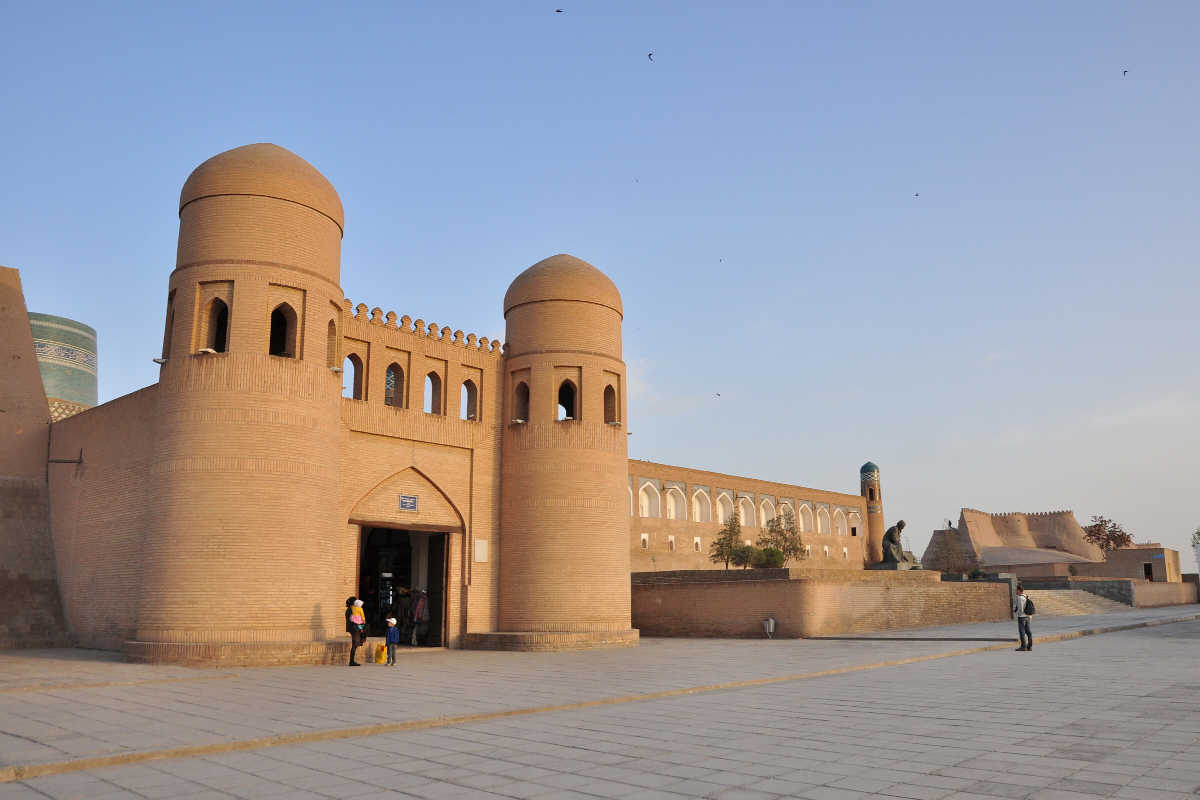

Extensive restoration work is currently underway to preserve this monumental building for future generations. In particular, the walls on the Registan Square side and numerous interior rooms have already been carefully restored. These measures ensure that Ark Citadel remains an important cultural heritage site and continues to captivate visitors from all over the world.

Extensive restoration work is currently underway to preserve this monumental building for future generations. In particular, the walls on the Registan Square side and numerous interior rooms have already been carefully restored. These measures ensure that Ark Citadel remains an important cultural heritage site and continues to captivate visitors from all over the world.